Post by Vitor Gaspar, Sanjeev Gupta and Carlos Mulas-Granados [1]

Every year, parliaments in democratic countries discuss budget proposals for the following year to set the course for economic policy going forward. But the reality is that politics and budgets are deeply interwoven. This was recognized by Joseph Schumpeter who noted “the spirit of a people, its cultural level, its social structure, the deeds its policy may prepare – all this and more is written in its fiscal history”. The crucial role of politics in economic decision making was also acknowledged by the leading American political scientist Harold Laswell when he said that politics is “the matter of who gets what, when and how”.

We delve deeper into the political economy of fiscal policy in a recent IMF book, “Fiscal Politics”. This book uses a new dataset that combines political and economic variables for over 90 countries—advanced as well as emerging and developing--spanning four decades. We find that proximity of elections and political divisions (for example, as reflected in thin parliamentary majority) are key to influencing policymakers conduct in formulating and implementing fiscal policy. That is, these two considerations determine the size and the composition of public budgets. Political ideology (whether the government has a left or right orientation), while important, is not as decisive, despite rhetorical disputes between political groups on opposite sides of the aisle in almost every country.

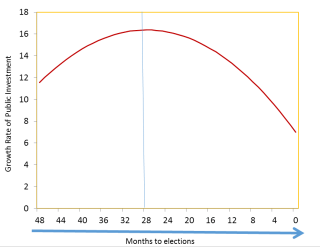

As elections approach, governments expand spending programs or reduce taxes to improve their chances of getting reelected. First, this is reflected in higher budget deficits (that is, expenditures exceed revenues by more than they would otherwise) by about 1 percentage points of GDP, with pressure coming from the wage side, particularly in emerging markets and low-income countries (e.g., Kenya and Moldova). Second, the electoral calendar affects the composition of spending programs. We find that the growth rate of public investment is larger at the beginning of the mandate, peaks about 28 months before elections, and then declines at 0.7 percentage points every month as one approaches elections (Figure 1). Electoral investment cycles can be observed both in advanced economies (e.g. Italy, the Netherlands or Portugal) and emerging and low-income countries (e.g. Croatia, Honduras, Slovakia or Zimbabwe).

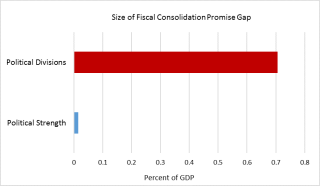

Political divisions can take different forms; a government can be divided because of a thin parliamentary majority, a high degree of cabinet fragmentation, or a strong opposition. We find that politically divided governments are unable to deliver on their budget promises. For example, the gap between planned fiscal deficit and actual results can be 7 times larger in divided governments than in governments with sizeable parliamentary majority (Figure 2). In the same vein, divided governments are associated with larger increases in spending, deficits and public debt as coalition members spend public resources to satisfy varied constituencies. For instance, during an average term, advanced economies where governments enjoyed a thin parliamentary majority experienced a higher increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio than their peers with larger parliamentary majority. A similar trend can be found in emerging market countries.

Figure 1. Proximity of Elections and Public investment

Source: Own elaboration. Data from Gaspar, Gupta and Mulas-Granados (2017), Fiscal Politics, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund. Chapter 5.

Figure 2. Political Divisions and Fiscal Consolidation Gap

Source: Own elaboration. Data from Gaspar, Gupta and Mulas-Granados (2017), Fiscal Politics, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund. Chapter 2.

Source: Own elaboration. Data from Gaspar, Gupta and Mulas-Granados (2017), Fiscal Politics, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund. Chapter 2.

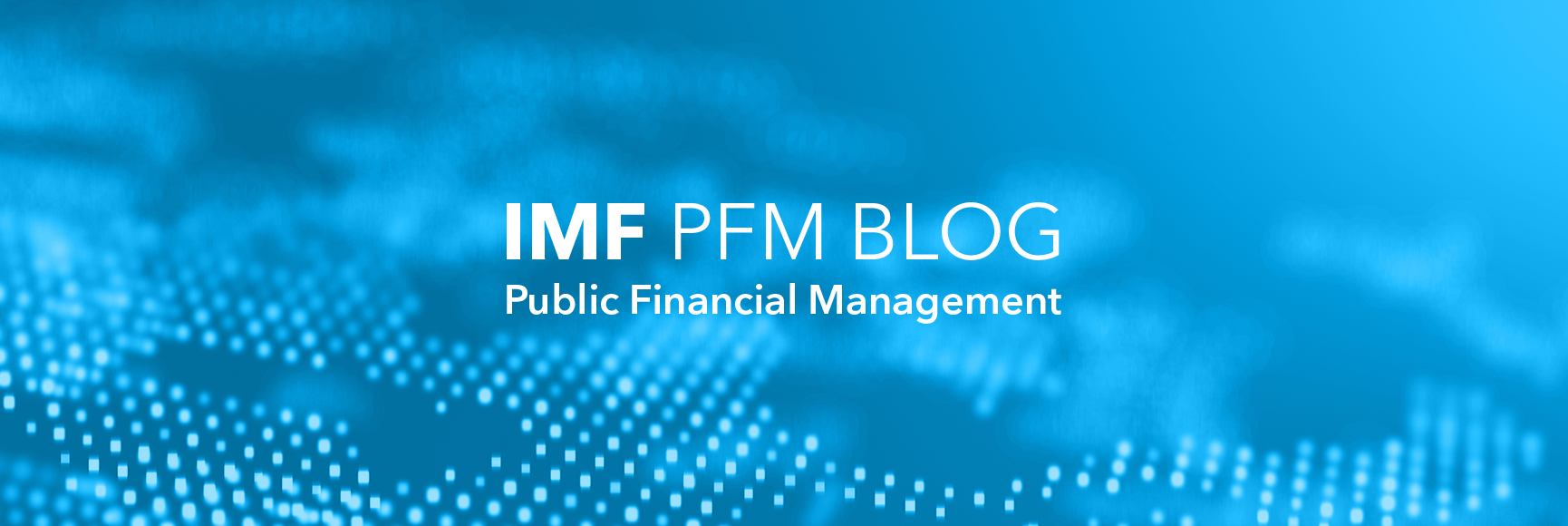

One would expect political ideology to drive fiscal outcomes. While partisan differences may explain the role of government in the economy, we did not find any evidence that ideology affects debt or deficit levels. We did find, however, that ideology matters for the composition of taxes and spending. For example, ideological partisanship affects tax policy responses during crises in advanced economies. A right-wing government is more likely to increase the VAT than a left government. A left government is more likely to increase the top personal income tax rate. Left-wing cabinets are positively and strongly associated with larger investment booms.

Figure 3. Ideology and Tax Changes During Banking Crises

Source: Own elaboration. Data from Gaspar, Gupta and Mulas-Granados (2017), Fiscal Politics, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund. Chapter 4.

Is there anything that can be done about the strong influence of politics on fiscal policy? Are fiscal rules and institutions capable of softening the impact of politics? The answer from the book is “yes”, but only partially. Evidence shows that expenditure rules reduce the volatility of expenditure associated with elections. And they are associated with better fiscal performance. The analysis of countries with independent fiscal councils shows that they have some positive influence on fiscal discipline, especially if their concerns are voiced in the media. The truth is that rules and institutions, both domestic and supranational, work only when countries own them and are committed to fiscal sustainability. Otherwise, political dynamics will make fiscal rules and institutions to fail.

[1] Vitor Gaspar is the Director of the Fiscal Affairs Department at the IMF, Sanjeev Gupta is the Deputy Director of the Fiscal Affairs Department and Carlos Mulas-Granados is a Senior Economist at the Fiscal Affairs Department

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.